Successful artificial insemination programs are based on a clear understanding of the anatomy and physiology of reproduction in cattle. Before attempting to inseminate cows, you must develop a mental picture of the anatomical parts that comprise the female

reproductive tract. In order to understand why an animal displays the many signs of estrus, when she should be inseminated, and how the pregnancy develops, you must clearly understand the hormonal mechanisms controlling the estrous cycle in cattle.

ANATOMY

First, let’s look at the parts that make up the reproductive system in cattle (Figure 1). There are two ovaries, two oviducts, two uterine horns, a uterine body, cervix, vagina and vulva. The bladder lies below the reproductive tract and is connected

at the urethral opening located on the vaginal floor. The rectum is located above the reproductive system.

The vulva is the external opening to the reproductive system. The vulva has three main functions: the passage of urine, the opening for mating and serves as part of the birth canal. Included in this structure are the lips and clitoris. The vulva

lips are located at the sides of the opening and appear wrinkled and dry when the cow is not in estrus. As the animal approaches estrus, the vulva will usually begin to swell and develop a moist red appearance.

The vagina, about six inches in length, extends from the urethral opening to the cervix. During natural mating, semen is

deposited in the anterior portion of the vagina. The vagina will also serve as part of the birth canal at the time of calving.

“In order to understand why an animal displays the many signs of estrus, when she should be inseminated, and how the pregnancy develops, you must clearly understand the hormonal mechanisms controlling the estrous cycle in cattle.”

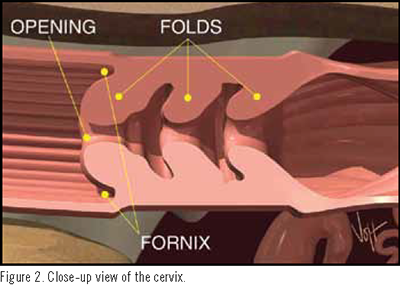

The

cervix is a thick-walled organ forming a connection between the vagina and uterus (Figure 2). It is composed of dense connective tissue and muscle and will be the primary landmark when inseminating cattle. The opening into the cervix protrudes back

into the vagina. This forms a 360º blind-ended pocket completely around the cervical opening. This pocket is referred to as the fornix. The interior of the cervix contains three to four annular rings or folds that facilitate the main function

of the cervix, which is to protect the uterus from the external environment. The cervix opens anteriorly into the uterine body. About an inch long, the body of the uterus serves as a connection between the two uterine horns and the cervix. The uterine

body is the site where semen should be deposited during artificial insemination.

The

cervix is a thick-walled organ forming a connection between the vagina and uterus (Figure 2). It is composed of dense connective tissue and muscle and will be the primary landmark when inseminating cattle. The opening into the cervix protrudes back

into the vagina. This forms a 360º blind-ended pocket completely around the cervical opening. This pocket is referred to as the fornix. The interior of the cervix contains three to four annular rings or folds that facilitate the main function

of the cervix, which is to protect the uterus from the external environment. The cervix opens anteriorly into the uterine body. About an inch long, the body of the uterus serves as a connection between the two uterine horns and the cervix. The uterine

body is the site where semen should be deposited during artificial insemination.

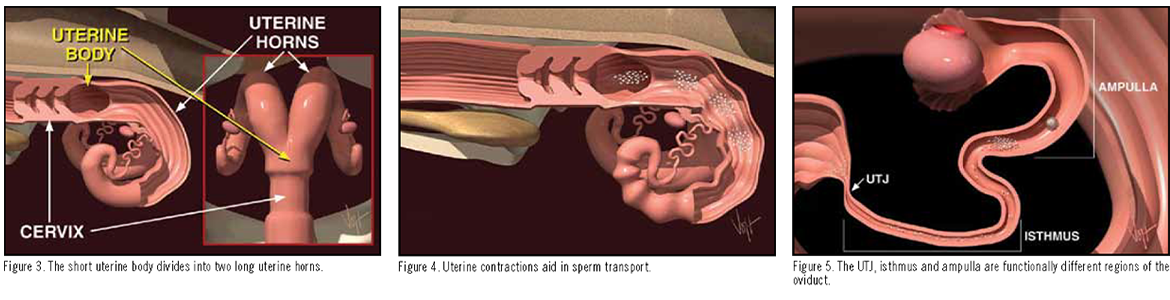

From the uterine body on, the reproductive tract separates and all further structures come in pairs (Figure 3). The two uterine horns consist of three layers of muscle and a heavy network of blood vessels. The main function of the uterus is to provide

a suitable environment for fetal development.

When a cow is bred, either naturally or by artificial insemination, the uterine muscles, under the influence of hormones oxytocin and estrogen, rhythmically contract to aid in sperm transport to the oviducts (Figure 4).

Oviducts, as their name implies, carry ova, the cow’s eggs. The oviducts are also commonly referred to as the fallopian tubes. The oviduct has several distinct regions when examined microscopically.

The lower segment, closest to the uterus is called the isthmus. The connection between the uterus and the isthmus is called the utero-tubal junction or UTJ. The UTJ functions as a filter of abnormal sperm and the isthmus as a reservoir for healthy sperm

(Figure 5).

Research suggests that upon gaining access to the isthmus, healthy spermatozoa attach themselves to the walls. During this period of attachment, many physiological changes occur to sperm membranes, which are essential to attainment of fertilization

potential. These changes are collectively referred to as capacitation and are apparently regulated by this very important attachment to the walls of the isthmus. It takes about five to six hours after insemination before a sufficient number of fertile

sperm cells can populate the isthmus and complete the capacitation process.

The upper portion of the oviduct, closest to the ovary, is referred to as the ampulla. The interior of the ampulla is more open than the isthmus allowing for easier passage of ova. It is within this segment of the oviduct that fertilization actually occurs.

It is believed that a chemical signal released at the time of ovulation, stimulates the release of spermatozoa from the walls of the isthmus allowing them to continue their journey to the site of fertilization in the ampulla.

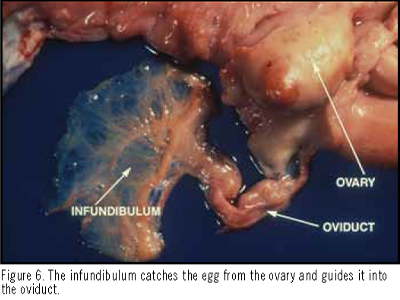

The large funnel-like structure on the open end of the oviduct, the infundibulum, surrounds the ovary, to recover the ova and keeps them from falling into the body cavity (Figure 6). Hairlike structures on the infundibulum and within the ampulla rhythmically

beat to move ova and a surrounding mass of cells called the cumulus mass down the oviduct to the site of fertilization (Figure 7).

The large funnel-like structure on the open end of the oviduct, the infundibulum, surrounds the ovary, to recover the ova and keeps them from falling into the body cavity (Figure 6). Hairlike structures on the infundibulum and within the ampulla rhythmically

beat to move ova and a surrounding mass of cells called the cumulus mass down the oviduct to the site of fertilization (Figure 7).

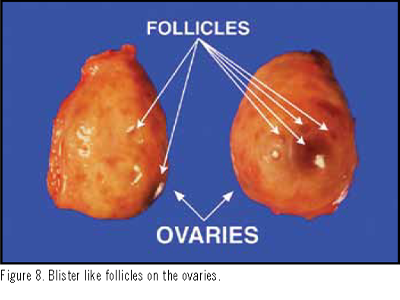

The ovaries are the primary organs in a cow’s reproductive tract. They have two functions: produce eggs and produce hormones, estrogen and progesterone, throughout the stages of the estrus cycle. On the surface of the ovary,

you will usually find two different types of structures.

Follicles are fluid filled, blister like structures that contain developing oocytes or eggs (Figure 8). Usually you will find numerous follicles on each ovary that vary in size from barely visible to ones 18 to 20mm in diameter. The largest follicle present

on one of the ovaries is termed the “dominant follicle” and is the most likely candidate for ovulation when the animal comes into heat. Over time, greater than 95 percent of the other follicles on the ovary regress and die without ovulating

and are replaced by new growing follicles.

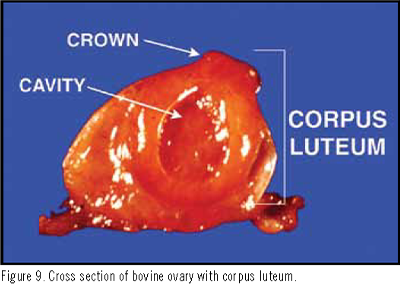

The other structure found on the ovarian surface is the corpus luteum or CL. The CL is the site where ovulation occurred during the previous cycle (Figure 9). Unless there were twin ovulations you should find only one CL located on one of the two ovaries.

The CL will usually have a distinct crown protruding from the ovarian surface, which facilitates identification during rectal palpation. The CL may also have a fluid filled cavity but usually has a much thicker wall than a follicle and thus a much

denser texture. “Corpus Luteum” is Latin for “yellow body.” While the outside of this structure is usually dark red in appearance, a cross section reveals a bright yellow to yellow-orange interior.

THE ESTROUS CYCLE

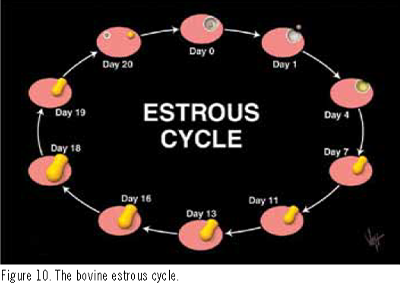

Over a period of time, many changes take place in the reproductive system in response to changing hormone levels. These changes in normal open females repeat every 18 to 21 days. This regular repetitive cycle is called the estrous cycle (Figure 10).

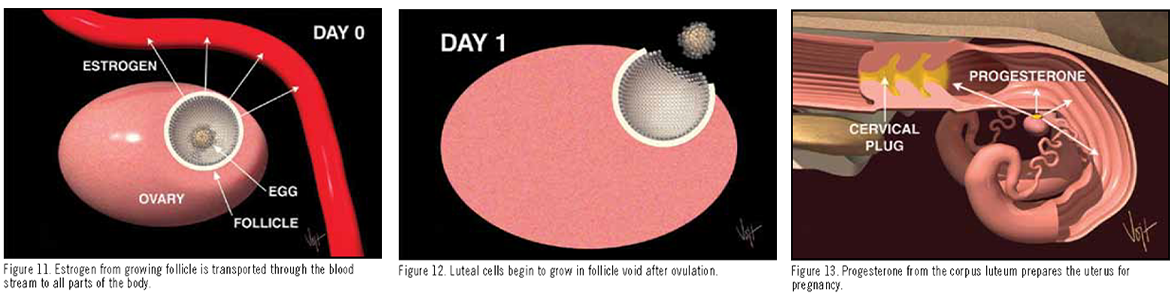

Let’s discuss how the estrous cycle works starting with a cow in heat on day zero. Looking at the reproductive tract, we see several things happening. One ovary has a large follicle approximately 15 to 20mm in diameter. This follicle has a mature

egg inside ready to be released. The cells lining the follicle are producing the hormone estrogen (Figure 11). Estrogen is transported in the blood stream to all parts of the cow’s body, causing other organs to react in a number of ways. It

makes the uterus more sensitive to stimulation and aids in the transport of semen at the time of insemination. It causes the cervix to secrete viscous mucus that flows and lubricates the vagina. Estrogen is also responsible for all signs of heat including;

a red swollen vulva, allowing other cows to mount her, going off feed, bellowing considerably and holding her ears erect are but a few of the many signs.

On day one, the follicle ruptures or “ovulates” releasing the egg to the waiting infundibulum (Figure 12). Several hours prior to ovulation estrogen production declines. As a result, the cow no longer displays the familiar signs of heat. After

ovulation, new types of cells called, luteal cells, grow in the void on the ovary where the follicle was located.

Quite rapidly over the next five to six days these cells grow to form the corpus luteum (CL). The CL produces another hormone, progesterone. Progesterone prepares the uterus for pregnancy (Figure 13). Under the influence of progesterone, the uterus produces

a nourishing substance for the embryo called uterine milk. At the same time, progesterone causes a thick mucous plug to form in the cervix, preventing access of bacteria or viruses into the uterus.

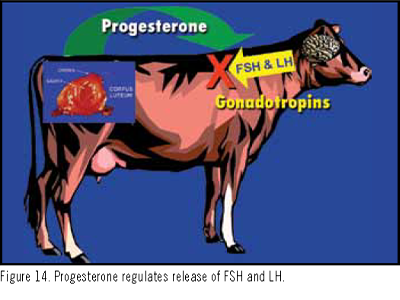

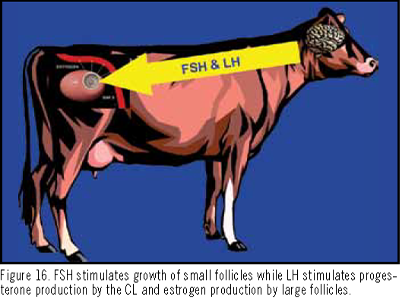

Progesterone also prevents the animal from returning to estrus by regulating the release of gonadotropins from the pituitary gland in the brain (Figure 14). There are two very important gonadotropins produced, stored and released from the pituitary gland.

The first is follicle stimulating hormone, or FSH. As its name implies FSH stimulates the growth of small follicles. Luteinizing hormone or LH is the other gonadotropin. In addition to supporting progesterone production by the CL, LH can also stimulate

estrogen production in large folicles. High levels of estrogen would bring the animal back into heat and make life difficult for a new embryo if she were pregnant. Thus, progesterone’s regulation of FSH and LH is a very important aspect of maintaining

the pregnancy.

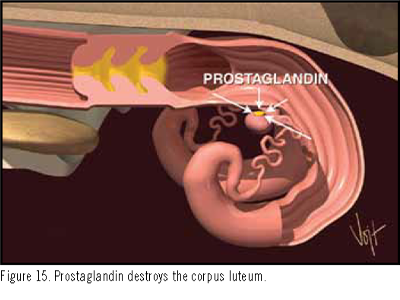

On the other hand, if we did not breed the cow, we do want her to come into heat again. Days 16 through 18 of the estrous cycle are referred to as “the period of maternal recognition.” During this time, the uterus searches itself for the presence

of a growing embryo. If no embryo is detected, the uterus begins to produce another hormone called prostaglandin. Prostaglandin begins to destroy the CL (Figure 15). When the CL is destroyed, no more progesterone is produced and the pituitary gland

begins to increase secretion of gonadotropins. Increased secretion of LH stimulates the dominant follicle to produce estrogen and bring the animal back into estrus (Figure 16).

A full cycle is now completed. The average total time is about 21 days. The estrous cycle is subdivided into two phases based on the dominant hormone or ovarian structure during each phase. The luteal phase begins  when the corpus luteum is formed; about

five to six days after the cow was in heat, and ends when the CL regresses, about day 17 to 19 of the cycle. Progesterone levels are high during this phase of the cycle and estrogen levels are low.

when the corpus luteum is formed; about

five to six days after the cow was in heat, and ends when the CL regresses, about day 17 to 19 of the cycle. Progesterone levels are high during this phase of the cycle and estrogen levels are low.

The other phase of the cycle; the follicular phase, begins when the CL of one cycle is regressed and ends when the new CL of the following cycle is formed. Thus, the follicular phase encompasses the period of time surrounding estrus (Figure 17). During

this phase of the cycle estrogen levels are typically high while progesterone levels are low.

As mentioned earlier, follicles may be present on the ovaries throughout the estrous cycle. Research using ultrasound technology has characterized follicular growth as occurring in “waves.” Normally, an animal will  have two or three waves

of follicular growth during a 21-day cycle (Figure 18). The beginning of each wave is characterized by a small rise in FSH followed by rapid growth of numerous follicles. From this wave of follicles, one follicle is selected to grow to a much larger

size than the others. This “dominant” follicle has the ability to regulate or restrict growth of all other follicles on the ovary. Dominant follicles only remain dominant for a short period of time, three to six days, which is followed

by either cell death and regression or ovulation and release of the egg. Consequently, disappearance of the dominant follicle coincides with recruitment of the next wave of follicular growth. From this new wave another dominant follicle will be

have two or three waves

of follicular growth during a 21-day cycle (Figure 18). The beginning of each wave is characterized by a small rise in FSH followed by rapid growth of numerous follicles. From this wave of follicles, one follicle is selected to grow to a much larger

size than the others. This “dominant” follicle has the ability to regulate or restrict growth of all other follicles on the ovary. Dominant follicles only remain dominant for a short period of time, three to six days, which is followed

by either cell death and regression or ovulation and release of the egg. Consequently, disappearance of the dominant follicle coincides with recruitment of the next wave of follicular growth. From this new wave another dominant follicle will be  selected.

selected.

Although it is typical for much follicular growth to occur throughout the estrous cycle, low levels of LH during the luteal phase, prevents these follicles from producing high levels of estrogen which would bring the animal ack into heat. It is only

the dominant follicle present at the time the CL regresses, when progesterone levels are low, that is permitted to produce enough estrogen to bring the animal back into estrus and to continue on to ovulation.

For the first four to five days, the embryo moves in the oviduct toward the uterus. Once the embryo gets there, it will be bathed in uterine fluids and continue to grow. While floating free in the uterus, several membranes, including the amnion, the chorion

and the allantois are produced by the early embryo. Collectively, these membranes are referred to as the placenta.

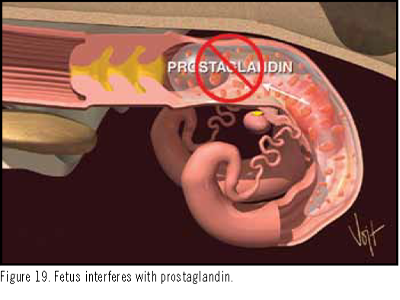

Hopefully, by the time the period of maternal recognition arrives, days 16 through 18, the fetus and growing placenta will have produced adequate quantities of the chemical signal required to maintain pregnancy. This signal interferes with the action

of prostaglandin on the corpus luteum (Figure 19). The CL is thus retained and continues to produce progesterone, which is essential to maintenance of the pregnancy.

At about 30 days of gestation, the placenta begins to attach to the uterus at several points. The placental sides of these attachment points are called cotyledons while the uterine side has caruncles. The attachment of cotyledons to caruncles is similar

to Velcro. This greatly increases the surface area within the attachment point, facilitating exchange of nutrients and waste products between calf and mother by way of arteries and veins leading to and through the umbilical cord.

At calving, the muscles in the uterus begin to contract and eventually expel the calf and membranes through a dilated cervix and vagina. Several hormones including progesterone, estrogen, prolactin, relaxin and corticoids produced by the mother, the fetus,

and the placenta, interact to bring about this event (Figure 20). Calving in a clean environment and proper treatment of the cow after a difficult calving will help prevent reproductive problems.

Becoming familiar with the reproductive anatomy and physiology of a cow will help you do a better job artificially inseminating your cattle. Understanding how the hormones involved in the estrous cycle interact to control this phenomenon gives you clearer

understanding why and when animals display the many signs of estrus, how pregnancy is maintained, and what you or your veterinarian must do to treat cows that do not cycle normally.

PDF IN ENGLISH